The artwork featured in this project are photographs taken of the surfaces of dumped burnt out cars.

Please Don’t Say It’s Rust

The artwork is not about rust, in fact, I reject images that have too much rust colour. I’m interested in the way the original paintwork is affected by fire and the changes to colours and the textures that are created.

This is my artist statement

My photography aims to capture the disturbance to surfaces created by acts of joyriding and arson by zooming into scorched, disfigured vehicle parts that are occupied in the lifecycle of corrosion, the natural process that tries to reclaim human made objects to an elemental state more in line with the energy of the molecules the objects are made of.

Torching accelerates this journey of returning to the earth and I look to capture, investigate and at times distort results of the advancement of its lifecycle. Using results of the explosion; scorched metal, molten glass, fabrics, and plastics, the rust and the gallons of water from the firemen’s hose I strive to turn a negative blot on the landscape using technology, photography and oil paint to transform the textual image into a positive beautiful landscape.

About the artwork

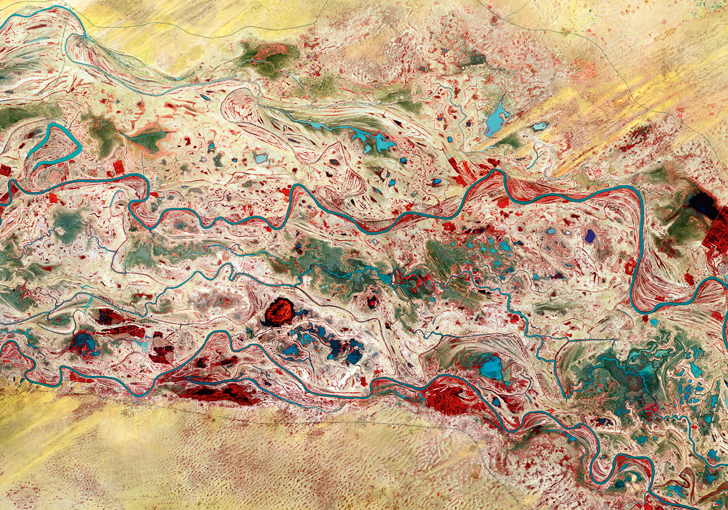

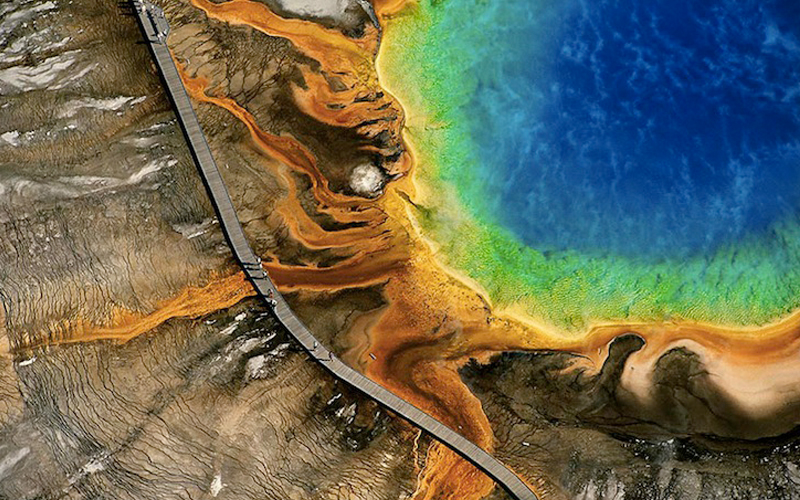

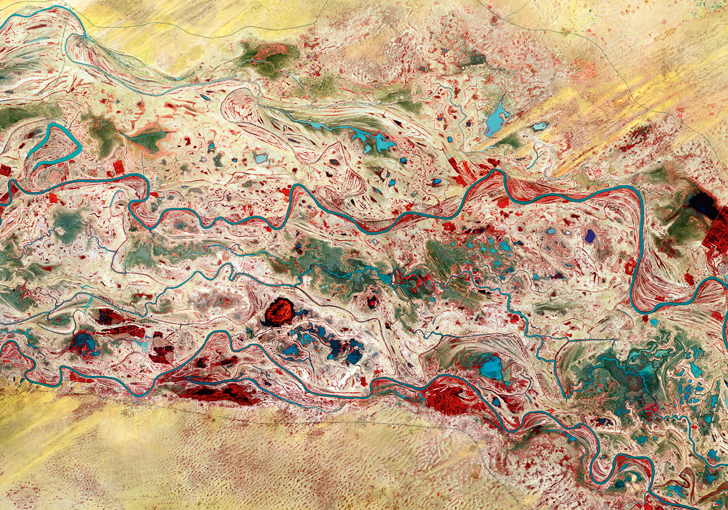

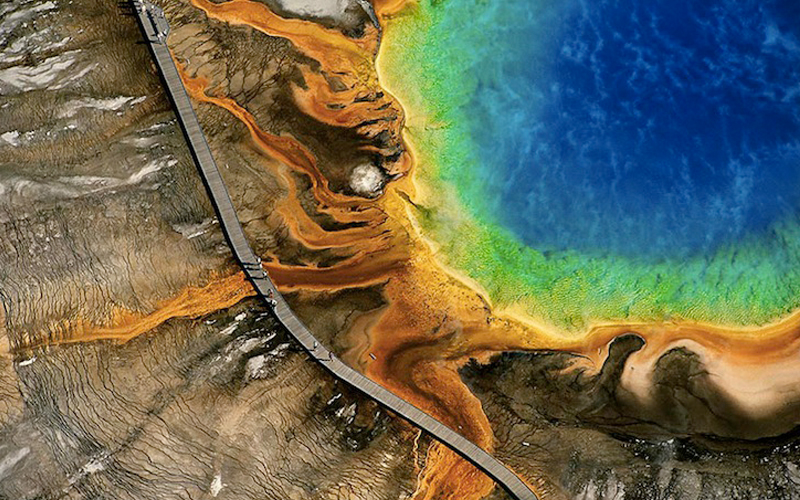

As I am looking through the lens photographing the surface of a burnt out car I am looking for a landscape of our earth taken from above. Sometimes that illusion comes naturally to me at that moment although if I see vibrant colour combinations I will take the shot and try re positioning the image in software later. OK sometimes that landscape isn’t there but there is a great image to appreciate and sometimes the viewer will interpret their own visualisation very different to me, perhaps seeing for example, the ocean, a face, or an animal, it doesn’t matter.

Although the natural reaction after the vehicle has been hosed by the firemen and then left open to the damp British weather is for the bare metal to become heavily rust covered. But in my images I try very hard to minimise the harsh reds and browns of rust and I concentrate on the distress to the car paint colours. The delicate scorch marks being more important than the bland flat surfaces of rust.

I have found that it is very important to photograph a vehicle within 48 hours of the fire. This is because the metal quickly loses its interesting markings that for example create shadow crevices like a relief map and the rust takes over completely. At this final stage the rust has a very bland, flat quality losing its markings. However, a few images on the site have been taken as long after the fire as 2 weeks because sometimes the rust can create a vibrant relief surface, that under the right lighting conditions is exactly what I want to achieve, therefore I can never say never.

Over the years I have produced this work, I have discovered that certain car models produce the most photogenic surfaces. The reasons for this is that during manufacturing each car company has different metal treatment processes and therefore every car will react completely differently when it is subjected to a further set of processes. The steel reacts differently under the extreme furnace heat of a car fire and this initial reaction is further shocked into change by the powerful icy cold jet from the fireman’s hose. This whole process is very important to my art models (which is how I always think of my cars). It is essential, because the thick ash surface needs to be cleaned by being jet washed by the power hose, leaving the bare metal to bend and twist as temperatures in different sections dive down, creating bends and huge dents on the landscapes.

There is nothing more exciting than seeing a burnt out van with scorch marks along the huge surface of the side panels. These are created by the wind pushing the flames through the side doors and licking the paint just enough.

History

People often ask me “how on earth did you think of photographing dumped burnt out cars”.

While passing a scrap yard in Tysley, Birmingham on a very wet day I noticed the rainwater cascading down the broken and squashed car bodies stacked about 8 cars high, I wanted to explore this image as a painting and so I took some photographs as reference material and then explored the possibility of old scrap cars being the subject of a project and to further this idea I visited other scrap yards in the area. During my research I looked at the paintings of John Salt a famous artist who incidentally, is also from Birmingham he focussed on images of cars, often shown wrecked or abandoned within a suburban or semi-rural American landscape.

During this period I was walking my dog along the river bank and came across a dumped burnt out car I saw this as an extension of the scrapyard project and I took 4 photographs at different perspectives of the car and about 10 close ups of the metal. (Now I will take as many as 1000 images and some videos of each car) I thought very little of it at the time but many months later began to “play around” with these images increasing the contrast and colour casts, and I got an immediate Wow reaction from the family in the room.

At that early stage of the project the images consisted of distorted car part images and judging the feedback from my audience I discovered that several people looking at my photographs could view a beautiful landscape of Pacific Islands taken from out of space, the complete opposite of the truth.

About this time the Yann Arthus-Bertrand “Earth From Above” exhibition was travelling the world and during its open air display in Birmingham I noticed through the very big high definition prints the potential for my own work to be concentrated even more as landscapes viewed from above in a plane, satellite, or spacecraft.

Images from Yann Arthus-Bertrand exhibition “Earth From Above”

Once the content had been established I then put considerable research into the presentation, I was after all a painter. But rather than just painting oil on canvas, I thought that because of the unique subject I wanted to let my imagination to invent something unique. I had read that the Disney Organisation had a department or team where they came up with weird and wonderful ideas and no originating idea however initially stupid it sounded was rejected until it had been tested, thoroughly. Therefore I decided I wanted to test my ideas.

First of all I tried to use car paint and reproduce the photo images on car bodywork, but I was always struggling to get any kind of reproduction that worked. The car paint was too harsh, didn’t lend itself to a mixture of layered colours and amongst other disadvantages the paint looked like a sticky plaster on the surface rather than a part of that surface.

I then looked to sculpture the artwork, but despite using metal, rag, glass and pieces made from plaster cast, again, something wasn’t right and getting materials and tools was proving to be very expensive. So, I returned once more to oil painting on a big canvas enhanced with three dimensional quality mixing sand, rag, rope, small pieces of glass and metals.

While producing the oil paintings I noticed that visitors to my studio were more interested in the original photographs that I was referencing. I never ever acknowledged photography as artwork. For me, it was a split second click of a shutter rather than months and months painting and building layers, then waiting for a coat to dry before I could add the next one. I just didn’t value photography. I wasn’t taking images, I was taking photographs to use as reference material I saw it as so much quicker than using my sketch pad.

Reluctantly I decided to market my original image, thinking that at least I could earn some money which I could reinvest into research. As l was still fighting this reluctance to accept photography as artwork, I knew I wanted to add value to the images. So, with this mind set, I started printing my work on sheet glass. I broke many sheets experimenting with the optimum thickness to print on while keeping the glass thin and therefore light enough to transport around the world.

The successful sales of my Fine Art photography meant I never did return to painting, not even as a hobby, because I don’t have time, I embraced photography and it became my art form as I worked on this project and then other subjects,

How Do I Get A Constant Supply Of Dumped Burnt Out Cars?

Obviously I needed more than one car to base a full time art career on, and in the early days it wasn’t that hard to find the wrecks. Within a short time, I developed an instinct for the parks and wasteland areas, as to where the burnouts could be. I would just drive around the West Midlands and notice a likely gap in a row of houses leading to garages or the side of the canal and there would be a car. But then, sadly for me, the supply of cars dried up

Because cars were towed away very quickly I decided to nurture contacts at the car salvage yards that the burn outs were taken to, this proved OK but not great. While handling the vehicles and dragging them onto the lorries and even worse, stacking them in the yards the cranes and chains used by the scrap yard workers damaged the surfaces that I wanted to preserve and photograph. They, of course, didn’t have the same precious concern about these beautiful models.

I then tried contacting the Fire Brigade stations direct, I called each fire station between 7am and 7:30 as the night shifts were just finishing and winding down. They then had time to talk, not just if they had attended a fire, but they would also give me background research on the areas of the city that were experiencing the most fires at that time. For a short period this process was very successful but then the West Midlands Fire Brigade telephone system became very centralised and I was unable to call the stations direct, I could have pursued it further, but I found another method was working.

I approached people who worked in, or visited the areas, that had historically produced sightings

of burnt out cars and asked them to telephone me if they found any.

There was John whose job is clearing litter and Fly Tipping rubbish from public parkland.

I asked many dog walkers while walking my own dogs. But by far the most productive scout has been Esther, who cycles everywhere and also designs cycle routes for Cycling For Beginners classes. Cyclists cut through where cars can’t go and this is where most of the dumping takes place. Esther and her daughter Imogen are brilliant. When they find a car I get a WhatsApp message, photo of the car and a location on Google Maps. This is not only brilliant, but essential, because the wreck could be anywhere, across a sports ground, or along a river bank well out of view from the nearest road.

Another regular burning area is in the inner city along the roads of back street garages and factories. Here I have the white van drivers who deliver to these backstreet garages and in the light of morning they can find the results of arson in the dark, quiet night streets.

The Accessibility and Location of a Burnt Out Is An Important Factor

Sometimes I don’t have the opportunity to photograph a burning car for a variety of reasons. For example a lack of access, the light and of course there was always the inherent danger of being so close to a burning car. This was true of the last two car fires that I attended. The engine of the first car caught fire while parked in the long stay car park at Birmingham Airport. It was in the evening and too dark to photograph the surfaces and there was also the factor that there were many purpose built vehicles and personal on site to clear the car so, unfortunately for me’ it was removed before the first light in the morning.

Another car was burnt out at the main entrance of the Fox Hollies Leisure Centre. As this is not the image they want to show schoolchildren attending swimming classes, it was reported and removed immediately. However, if the fire had taken place on the far side of the car park, out of sight and rarely used, it would have remained there long enough for me to get some photographs. Only on one occasion did I come across a car but didn’t have a camera, I now carry a camera everywhere I go.

Once I found a van with the best scorch marks I have ever seen but I needed a step ladder to get up on the correct level, in the 20 minutes it took me to go home and get my steps, the van had gone.

As Well As Finding Burnt Out Cars, I Burn My Own

I have been asked on many occasions do I ever torch the cars? Well, the answer is no, I don’t.

When attending a car fire the fire brigade have to isolate the fire in the engine as soon as possible, in order to make the incident safe and when they do this I noticed that they would often leave pieces of metal debris at the side of the burnt out car. I decided to take these panels home to photograph at a later date. I had accumulated quite a pile dumped at the bottom of the garden, some being a few years old and in that state they were useless. So, I started to work cleaning the panels and this produced some interesting results, which was a little bit different to the new burnt out metal but in a similar genre.

I spent months developing this work, noticeably during a period when the burnt out cars were a little bit scarce and I was worried my supply would dry up. I carried out experiments burning metal by using small blow torches, or a bed of charcoal, and I even tried putting the metal on the garden bonfire. I experimented on painting the surfaces, although this never worked because I found the paint would blend into the metal surface and it looked like another flat layer on the metal. I tried using acid solutions in order to clean the marks, but leave the corrosive contours. I used varying different strengths of acid, as sometimes I wanted a very quick full clean, while other times I wanted it to take a long time so that I could measure the effects as I go. I found that Coca Cola and HP Sauce have great acid values when I want a very slow process.

As you know, generally oil and water don’t mix but they can create beautiful colours. This is often true of other substances found around the home. For example, I will often pick something like linseed oil and coat it with WD40 to see how it looks. I raid garage workshops for any liquids such as engine cleaner, brake fluids. I’m always interested when new household products such as fly spray, bleaches or cleaning products come on the market along with natural products like the juice of a lemon. I try to stay away from rust but sometimes I will actively encourage it. Perhaps by soaking a sponge in salt water and letting it slowly drip across the metal, and if I see something I like, I will preserve it by spraying varnish on the area.

When I see a metal area that is just right, then I get my camera ready and now, ideally, I can position myself comfortably. As you can imagine when I’m working on a car “in the field” I have to make do with the available lighting conditions, intrusive shadows interfering across the perfect point of view and a never ideal height or angle (I have known a situation when to photograph a great surface I had to hang upside down over a car, yes it was worth it). Of course, in the garden I’m never working under the pressure of the car being towed away before my eyes as I try to get the final images on camera.

Photographing metal in these “roll your own” conditions is more precise and controlled. I generally experiment in the garden and during the daily throwing of the ball for my dog’s exercise, I view the metal in different lights and angles, as the journey of decay and corrosion continue. I keep an eye on it until the metal develops into an image that I am happy with. At this point when everything comes together, I can set up photo studio conditions using lights, reflectors, and/or gels, working with a tripod and position the metal in the right angle for the shot. However, sometimes the metal may never get to the photograph stage and I am often frustrated when markings on a surface look initially promising, but ends up being a let down when seen through the lens or on my computer screen.

I’m always on the lookout for car metal and avoid paying the scrap dealers, and when I replace my car one of the deciding options on a purchase is the amount of room in the back and can I get a bonnet in there or even strapped down on the roof.

The artwork featured in this project are photographs taken of the surfaces of dumped burnt out cars.

Please Don’t Say It’s Rust

The artwork is not about rust, in fact, I reject images that have too much rust colour. I’m interested in the way the original paintwork is affected by fire and the changes to colours and the textures that are created.

This is my artist statement

My photography aims to capture the disturbance to surfaces created by acts of joyriding and arson by zooming into scorched, disfigured vehicle parts that are occupied in the lifecycle of corrosion, the natural process that tries to reclaim human made objects to an elemental state more in line with the energy of the molecules the objects are made of.

Torching accelerates this journey of returning to the earth and I look to capture, investigate and at times distort results of the advancement of its lifecycle. Using results of the explosion; scorched metal, molten glass, fabrics, and plastics, the rust and the gallons of water from the firemen’s hose I strive to turn a negative blot on the landscape using technology, photography and oil paint to transform the textual image into a positive beautiful landscape.

About the artwork

As I am looking through the lens photographing the surface of a burnt out car I am looking for a landscape of our earth taken from above. Sometimes that illusion comes naturally to me at that moment although if I see vibrant colour combinations I will take the shot and try re positioning the image in software later. OK sometimes that landscape isn’t there but there is a great image to appreciate and sometimes the viewer will interpret their own visualisation very different to me, perhaps seeing for example, the ocean, a face, or an animal, it doesn’t matter.

Although the natural reaction after the vehicle has been hosed by the firemen and then left open to the damp British weather is for the bare metal to become heavily rust covered. But in my images I try very hard to minimise the harsh reds and browns of rust and I concentrate on the distress to the car paint colours. The delicate scorch marks being more important than the bland flat surfaces of rust.

I have found that it is very important to photograph a vehicle within 48 hours of the fire. This is because the metal quickly loses its interesting markings that for example create shadow crevices like a relief map and the rust takes over completely. At this final stage the rust has a very bland, flat quality losing its markings. However, a few images on the site have been taken as long after the fire as 2 weeks because sometimes the rust can create a vibrant relief surface, that under the right lighting conditions is exactly what I want to achieve, therefore I can never say never.

Over the years I have produced this work, I have discovered that certain car models produce the most photogenic surfaces. The reasons for this is that during manufacturing each car company has different metal treatment processes and therefore every car will react completely differently when it is subjected to a further set of processes. The steel reacts differently under the extreme furnace heat of a car fire and this initial reaction is further shocked into change by the powerful icy cold jet from the fireman’s hose. This whole process is very important to my art models (which is how I always think of my cars). It is essential, because the thick ash surface needs to be cleaned by being jet washed by the power hose, leaving the bare metal to bend and twist as temperatures in different sections dive down, creating bends and huge dents on the landscapes.

There is nothing more exciting than seeing a burnt out van with scorch marks along the huge surface of the side panels. These are created by the wind pushing the flames through the side doors and licking the paint just enough.

History

People often ask me “how on earth did you think of photographing dumped burnt out cars”.

While passing a scrap yard in Tysley, Birmingham on a very wet day I noticed the rainwater cascading down the broken and squashed car bodies stacked about 8 cars high, I wanted to explore this image as a painting and so I took some photographs as reference material and then explored the possibility of old scrap cars being the subject of a project and to further this idea I visited other scrap yards in the area. During my research I looked at the paintings of John Salt a famous artist who incidentally, is also from Birmingham he focussed on images of cars, often shown wrecked or abandoned within a suburban or semi-rural American landscape.

During this period I was walking my dog along the river bank and came across a dumped burnt out car I saw this as an extension of the scrapyard project and I took 4 photographs at different perspectives of the car and about 10 close ups of the metal. (Now I will take as many as 1000 images and some videos of each car) I thought very little of it at the time but many months later began to “play around” with these images increasing the contrast and colour casts, and I got an immediate Wow reaction from the family in the room.

At that early stage of the project the images consisted of distorted car part images and judging the feedback from my audience I discovered that several people looking at my photographs could view a beautiful landscape of Pacific Islands taken from out of space, the complete opposite of the truth.

About this time the Yann Arthus-Bertrand “Earth From Above” exhibition was travelling the world and during its open air display in Birmingham I noticed through the very big high definition prints the potential for my own work to be concentrated even more as landscapes viewed from above in a plane, satellite, or spacecraft.

Images from Yann Arthus-Bertrand exhibition “Earth From Above”

Once the content had been established I then put considerable research into the presentation, I was after all a painter. But rather than just painting oil on canvas, I thought that because of the unique subject I wanted to let my imagination to invent something unique. I had read that the Disney Organisation had a department or team where they came up with weird and wonderful ideas and no originating idea however initially stupid it sounded was rejected until it had been tested, thoroughly. Therefore I decided I wanted to test my ideas.

First of all I tried to use car paint and reproduce the photo images on car bodywork, but I was always struggling to get any kind of reproduction that worked. The car paint was too harsh, didn’t lend itself to a mixture of layered colours and amongst other disadvantages the paint looked like a sticky plaster on the surface rather than a part of that surface.

I then looked to sculpture the artwork, but despite using metal, rag, glass and pieces made from plaster cast, again, something wasn’t right and getting materials and tools was proving to be very expensive. So, I returned once more to oil painting on a big canvas enhanced with three dimensional quality mixing sand, rag, rope, small pieces of glass and metals.

While producing the oil paintings I noticed that visitors to my studio were more interested in the original photographs that I was referencing. I never ever acknowledged photography as artwork. For me, it was a split second click of a shutter rather than months and months painting and building layers, then waiting for a coat to dry before I could add the next one. I just didn’t value photography. I wasn’t taking images, I was taking photographs to use as reference material I saw it as so much quicker than using my sketch pad.

Reluctantly I decided to market my original image, thinking that at least I could earn some money which I could reinvest into research. As l was still fighting this reluctance to accept photography as artwork, I knew I wanted to add value to the images. So, with this mind set, I started printing my work on sheet glass. I broke many sheets experimenting with the optimum thickness to print on while keeping the glass thin and therefore light enough to transport around the world.

The successful sales of my Fine Art photography meant I never did return to painting, not even as a hobby, because I don’t have time, I embraced photography and it became my art form as I worked on this project and then other subjects,

How Do I Get A constant Supply Of Dumped Burnt Out Cars?

Obviously I needed more than one car to base a full time art career on, and in the early days it wasn’t that hard to find the wrecks. Within a short time, I developed an instinct for the parks and wasteland areas, as to where the burnouts could be. I would just drive around the West Midlands and notice a likely gap in a row of houses leading to garages or the side of the canal and there would be a car. But then, sadly for me, the supply of cars dried up

Because cars were towed away very quickly I decided to nurture contacts at the car salvage yards that the burn outs were taken to, this proved OK but not great. While handling the vehicles and dragging them onto the lorries and even worse, stacking them in the yards the cranes and chains used by the scrap yard workers damaged the surfaces that I wanted to preserve and photograph. They, of course, didn’t have the same precious concern about these beautiful models.

I then tried contacting the Fire Brigade stations direct, I called each fire station between 7am and 7:30 as the night shifts were just finishing and winding down. They then had time to talk, not just if they had attended a fire, but they would also give me background research on the areas of the city that were experiencing the most fires at that time. For a short period this process was very successful but then the West Midlands Fire Brigade telephone system became very centralised and I was unable to call the stations direct, I could have pursued it further, but I found another method was working.

I approached people who worked in, or visited the areas, that had historically produced sightings

of burnt out cars and asked them to telephone me if they found any.

There was John whose job is clearing litter and Fly Tipping rubbish from public parkland.

I asked many dog walkers while walking my own dogs. But by far the most productive scout has been Esther, who cycles everywhere and also designs cycle routes for Cycling For Beginners classes. Cyclists cut through where cars can’t go and this is where most of the dumping takes place. Esther and her daughter Imogen are brilliant. When they find a car I get a WhatsApp message, photo of the car and a location on Google Maps. This is not only brilliant, but essential, because the wreck could be anywhere, across a sports ground, or along a river bank well out of view from the nearest road.

Another regular burning area is in the inner city along the roads of back street garages and factories. Here I have the white van drivers who deliver to these backstreet garages and in the light of morning they can find the results of arson in the dark, quiet night streets.

The Accessibility and Location of a Burnt Out Is An Important Factor

Sometimes I don’t have the opportunity to photograph a burning car for a variety of reasons. For example a lack of access, the light and of course there was always the inherent danger of being so close to a burning car. This was true of the last two car fires that I attended. The engine of the first car caught fire while parked in the long stay car park at Birmingham Airport. It was in the evening and too dark to photograph the surfaces and there was also the factor that there were many purpose built vehicles and personal on site to clear the car so, unfortunately for me’ it was removed before the first light in the morning.

Another car was burnt out at the main entrance of the Fox Hollies Leisure Centre. As this is not the image they want to show schoolchildren attending swimming classes, it was reported and removed immediately. However, if the fire had taken place on the far side of the car park, out of sight and rarely used, it would have remained there long enough for me to get some photographs. Only on one occasion did I come across a car but didn’t have a camera, I now carry a camera everywhere I go.

Once I found a van with the best scorch marks I have ever seen but I needed a step ladder to get up on the correct level, in the 20 minutes it took me to go home and get my steps, the van had gone.

As Well As Finding Burnt Out Cars, I Burn My Own

I have been asked on many occasions do I ever torch the cars? Well, the answer is no, I don’t.

When attending a car fire the fire brigade have to isolate the fire in the engine as soon as possible, in order to make the incident safe and when they do this I noticed that they would often leave pieces of metal debris at the side of the burnt out car. I decided to take these panels home to photograph at a later date. I had accumulated quite a pile dumped at the bottom of the garden, some being a few years old and in that state they were useless. So, I started to work cleaning the panels and this produced some interesting results, which was a little bit different to the new burnt out metal but in a similar genre.

I spent months developing this work, noticeably during a period when the burnt out cars were a little bit scarce and I was worried my supply would dry up. I carried out experiments burning metal by using small blow torches, or a bed of charcoal, and I even tried putting the metal on the garden bonfire. I experimented on painting the surfaces, although this never worked because I found the paint would blend into the metal surface and it looked like another flat layer on the metal. I tried using acid solutions in order to clean the marks, but leave the corrosive contours. I used varying different strengths of acid, as sometimes I wanted a very quick full clean, while other times I wanted it to take a long time so that I could measure the effects as I go. I found that Coca Cola and HP Sauce have great acid values when I want a very slow process.

As you know, generally oil and water don’t mix but they can create beautiful colours. This is often true of other substances found around the home. For example, I will often pick something like linseed oil and coat it with WD40 to see how it looks. I raid garage workshops for any liquids such as engine cleaner, brake fluids. I’m always interested when new household products such as fly spray, bleaches or cleaning products come on the market along with natural products like the juice of a lemon. I try to stay away from rust but sometimes I will actively encourage it. Perhaps by soaking a sponge in salt water and letting it slowly drip across the metal, and if I see something I like, I will preserve it by spraying varnish on the area.

When I see a metal area that is just right, then I get my camera ready and now, ideally, I can position myself comfortably. As you can imagine when I’m working on a car “in the field” I have to make do with the available lighting conditions, intrusive shadows interfering across the perfect point of view and a never ideal height or angle (I have known a situation when to photograph a great surface I had to hang upside down over a car, yes it was worth it). Of course, in the garden I’m never working under the pressure of the car being towed away before my eyes as I try to get the final images on camera.

Photographing metal in these “roll your own” conditions is more precise and controlled. I generally experiment in the garden and during the daily throwing of the ball for my dog’s exercise, I view the metal in different lights and angles, as the journey of decay and corrosion continue. I keep an eye on it until the metal develops into an image that I am happy with. At this point when everything comes together, I can set up photo studio conditions using lights, reflectors, and/or gels, working with a tripod and position the metal in the right angle for the shot. However, sometimes the metal may never get to the photograph stage and I am often frustrated when markings on a surface look initially promising, but ends up being a let down when seen through the lens or on my computer screen.

I’m always on the lookout for car metal and avoid paying the scrap dealers, and when I replace my car one of the deciding options on a purchase is the amount of room in the back and can I get a bonnet in there or even strapped down on the roof.